When the System Surprises You

On emergence, authorship, and the quiet astonishment of generative art

[I formulated this idea for a paper I presented at UPES in 2023.]

The study of generative art arrived in my work through teaching. While designing a postgraduate course on art and technology, I found myself confronted with a curious category of works: visual artefacts generated not by hand, but by system. These were unmistakably aesthetic, sometimes astonishingly so.

The question I began with was deceptively simple: how do we study art that was not composed in the traditional sense, but emerged?

Generative art, in one of its more widely accepted definitions, is art in which an autonomous system contributes materially to the output. It is not random, nor is it fully authored. It sits somewhere in between. The artist constructs the constraints, sets the process in motion, but the final form is unknown until it appears. This unknowability — what systems theorists call emergence — is not a failure of control. It is the very condition of generativity.

Let me make this concrete.

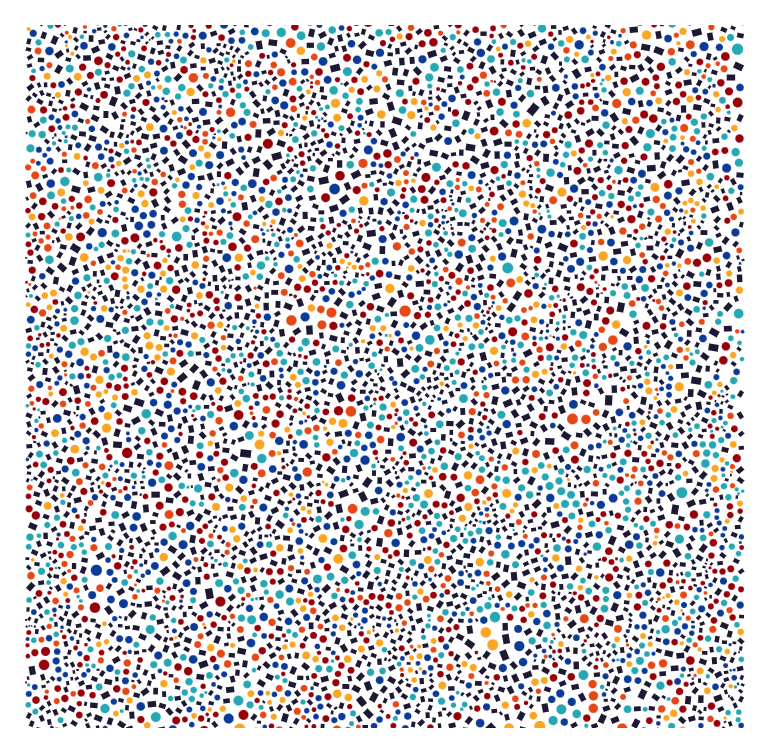

I once wrote a program to generate an image I titled Barcelona. It is built on a system of Voronoi tessellations. The visual outcome, an abstract composition of coloured circles and black rectangles, is produced by distributing 6000 points across a canvas. These points are not randomly scattered, but weighted by the brightness values of a hidden reference image. Five colours are used. Each run of the program creates a new composition. No two are alike.

To an external observer, Barcelona might seem composed, even calculated. But I know better. I know that while I chose the colours, the number of points, and the structure of the algorithm, I cannot determine the final image. I can control the rules, not the result.

This is emergence. And it manifests in two distinct modes.

In one, objective emergence, we acknowledge the limits of our predictive power. The system behaves in ways that cannot be reduced to simpler descriptions. The only way to know what it will do is to run it. This is a familiar intuition to anyone who has worked in data analysis: simulation becomes epistemology.

In the other, subjective emergence, the system surprises even when we understand it completely. It is not our ignorance that produces mystery, but the aesthetics of perception. We are startled by what we already know.

Both modes challenge traditional ideas of authorship. They also challenge how we evaluate art. If each run of the algorithm generates a different output, which one is the work? If surprise is engineered, does it lose its value?

Perhaps most provocatively, emergence invites us to reconsider the role of the artist. The value of a generative work lies not in its uniqueness, but in its capacity to generate uniqueness within constraint. The artist becomes less a composer and more a constructor of possibility.

This, too, has implications for how we study such works. To appreciate a generative piece is not merely to look at it, but to understand the system that gave rise to it. In that sense, the aesthetics of generative art are inseparable from its mechanics. The code is not behind the art: it is the art.

Some critics have argued that such works lack soul. That if emotion is absent at the point of generation, it cannot be recovered by the viewer. But this misunderstands the nature of system-based creation. Every line of code is a decision, every constraint a gesture. The emergence of form does not negate its meaning. It refracts it.

The ink painting left to bleed. The salt print slowly darkening. The algorithm letting go. These are not separate categories. They are all moments where something more is produced than what was put in.

And if we are moved by what we see, does it really matter how it was made?